Best & Notable Releases of 2012

My picks from the hundreds of new releases I received in 2012.

Read MoreMy picks from the hundreds of new releases I received in 2012.

Read MoreMy favorite releases of 2011.

Read More“I remember Bob Brozman sayin' that any modern guitar player, contemporary guitar player, that plays finger-style country blues-influenced guitar who says he's not influenced by John Fahey is a bullshit artist,” was bluesman Steve James' response to the query whether he had listened to the work of John Fahey.

Read MoreI am occasionally asked why my professional card, letterhead, website, and blog are headed by the phrase “I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say. . . .” Sometimes, a person will inquire, “Who is Buddy Bolden?” Well, the phrase comes from, “Buddy Bolden’s Blues,” which was originally titled "Funky Butt" when it was a song in the repertoire of New Orleans cornetist and bandleader Charles “Buddy” Bolden (1877-1931), the legendary father of jazz. You can read about Buddy here. For further reading, I recommend Donald Marquis’s In Search Of Buddy Bolden: First Man Of Jazz and Danny Barker’s Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville.

Some consider "Funky Butt” the oldest known jazz tune. It was Jelly Roll Morton (1885-1941) who bestowed the title “Buddy Bolden’s Blues” upon it and fashioned his own lyrics. Jelly made two commercial recordings of the song, in 1939, rendering it as a solo piano piece and as a band number. It is also included in the epic 1938 Library of Congress session that folklorist Alan Lomax recorded of Morton telling the story of his life, providing an account of the early years of jazz, and expatiating upon New Orleans history, all to the accompaniment of his piano. Jelly does the vocal on all three versions. And here is what he sings:

Buddy Bolden’s Blues (Lyrics by Jelly Roll Morton)

I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say You nasty, you dirty—take it away You terrible, you awful—take it away I thought I heard him say

I thought I heard Buddy Bolden shout Open up that window and let that bad air out Open up that window, and let the foul air out I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say

I thought I heard Judge Fogarty say Thirty days in the market—take him away Get him a good broom to sweep with—take him away I thought I heard him say

I thought I heard Frankie Dusen shout Gal, give me that money—I’m gonna beat it out I mean give me that money, like I explain you, or I’m gonna beat it out I thought I heard Frankie Dusen say

Jelly Roll Morton has long been one of my main jazz heroes. In a 1945 letter that I wrote to my older brother Turner I told of several recent 78 rpm record acquisitions. I was fifteen at the time and had been obsessed with jazz for three years. In the course of a visit to Baltimore’s General Radio and Record Shop, “I miraculously ran across a reprint of an out-of-date Jelly Roll Morton piano solo album which contains ten sides and costs $4.72. His name practically means jazz he’s so famous. He’s a famous New Orleans blues piano artist who’s been dead for four years. . . . The album is terrific.”

I began my decade and a half on radio in late 1972 in Washington, D.C., playing early jazz selections as a Monday guest of WGTB-FM’s three-hour Spritus Cheese, hosted by Mark Gorbulew. The second week into my several-month ride on Spiritus Cheese, Mark turned to me as he prepared to open the show and asked what I would like to call my feature. He gave me no more than a few seconds to come up with a name before going on air. I blurted out what came to mind, Mark flipped a switch and, leaning forward to the mike, announced, “Mark Gorbulew here with Spritus Cheese this beautiful afternoon, and once again we have with us Royal Stokes and his ‘I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say. . . ,’ an hour of old jazz records culled from his personal collection.” I soon had my own Saturday morning three-hour slot and, of course, I called it “I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say . . . .”

The phrase has always seemed to me an apt metaphor for all that followed in the wake of Jelly Roll Morton’s major contributions to the jazz idiom. He was not only a virtuoso pianist and pioneer bandleader but, in Martin Williams’s term, “the first master of form in jazz.” You can read about Jelly here.

Solo piano version of "Buddy Bolden's Blues":

Band arrangement of "Buddy Bolden's Blues":

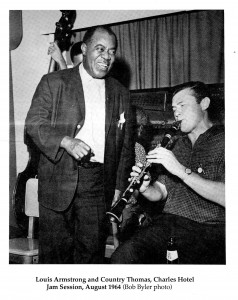

My friend of six decades Mason "Country" Thomas, whom I first met and saw perform at a Sunday afternoon jam session in January 1950 at Louie’s and Alex’s on U Street in Washington, D.C., died on August 24, 2011.

My friend of six decades Mason "Country" Thomas, whom I first met and saw perform at a Sunday afternoon jam session in January 1950 at Louie’s and Alex’s on U Street in Washington, D.C., died on August 24, 2011.

While his main horns were clarinet and tenor and baritone saxophones, at one time or another Country also played soprano and bass saxophones, trumpet, trombone, tuba, and bass fiddle. I was at a Blindfold record session at D.C.’s Charles Hotel on 14th Street (a venerable jazz venue of the 1950s-1970s) one Sunday night in 1951 when nobody could identify the piano player on the 78 rpm that was played. It turned out to be a home-recorded disc of Country, churning out some hot boogie woogie. Incidentally, with perfect pitch and an uncanny ear, Country could hear a tune once or twice and render it with all its nuances. He was also something of a Renaissance man, holding down a day gig as an air-conditioner and refrigeration serviceman. Another of his talents, I was once told by a fellow musician of his, was fashioning reeds for clarinets and saxophones. Country could repair anything mechanical -- automobile engines, washing machines, you name it.

Country played in many Washington-area bands, for example, the Washington Monumentals and bands led by his close musical associate, cornetist Wild Bill Whelan. Country was a regular presence at both the annual Manassas Jazz Festival (1960s-1980s) and the Potomac River Jazz Club’s annual all-day-and-evening picnic at Blob’s Park in September, sometimes in more than one band. Over the course of his career, Country played most of the jazz venues in the D.C. area. And whenever any of the Eddie Condon gang (e.g., Wild Bill Davison, Bill Whelan’s mentor) came to D.C. for gigs, you would always find Country on the bandstand with them. For them, he was first-call reed player. Country remained musically active into his eighties.

Country had a long-time close musical relationship with cornetist Wild Bill Whelan, who died in 2003. Here’s Country taking a solo after Whelan.

Here is a slide show with Country playing “Willow Weep For Me” on tenor.

Here is the Washington Post obituary of Country.

And below is the text of my March 1984 Washington Post feature on Country.

Mason "Country" Thomas, Multi-Instrumentalist

By W. Royal Stokes

The countless Washington-area bandstands that have cooked with small combos of which multi-instrumentalist Mason "Country" Thomas was either a member or the leader add up to very nearly a complete roster of D.C. jazz venues of the past four decades [i.e., 1940s-1980s]. They include after-hours clubs like the Villa Bea, hole-in-the-wall but star-studded clubs like the Brown Derby, high-end restaurants such as downtown D.C.’s Blue Mirror and Georgetown’s Blue Alley, and all the major hotels. Thomas’s trio presently holds forth Mondays through Saturdays in the Garden Lounge of the new J. W. Marriott Hotel at 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue.

A registered member of the after-hours “bottle club” Villa Bea at 19th and California in Adams Morgan, with his personal bottle of whiskey on the shelf behind the bar, Thomas often played there. One night in the early 1940s, before he entered the army, he played clarinet until dawn with a pianist who, he later learned, was Erroll Garner. “He wasn’t famous yet,” says Thomas, “so I didn’t know who he was.”

Thomas, a native of this city [D.C.], grew up in Arlington, attending Washington and Lee High School and then Augusta Military Academy in Staunton, Virginia. He made up his mind in his mid-teens to become a musician upon hearing on radio the clarinet of Artie Shaw. “I always had a keen interest in music,” he explains. “My mother played piano, my father picked guitar and they would have parties where there was a lot of barbershop singing and some people would bring in horns and they’d have kind of jam sessions. They were playing old songs like ‘Somebody Stole My Gal’ and ‘There’ll Be Some Changes Made.’ I knew all those songs before I ever pick up a horn.”

Purchase of a $10 clarinet and introduction to small-band jazz via the record collection of a schoolmate were the first steps in Thomas’ self-instruction, subsequently augmented by formal training at the Brooklyn Conservatory of music. He has played all the saxophones professionally except the alto and at one time or another has earned his living playing trumpet, trombone, tuba, and upright bass. As a youngster he took piano lessons and along the way has “picked some guitar.”

“My god, you couldn’t walk down the street without bumping into all these luminaries,” recalls Thomas of strolls down New York’s 52nd Street in 1943 just before he went into the army to serve as a rifleman-grenadier in Europe in WW2. Thomas made friends as a teenager visiting New York with the likes of saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, guitarist and bandleader Eddie Condon, and clarinetists Mezz Mezzrow and Pee Wee Russell, the latter a major stylistic influence on him. “Those guys were really something else in those days “cause we were just kids and they treated us like we were the greatest thing in the world, buying us food and everything and watching after us to make sure nothing bad happened to us.”

When Thomas returned from the war he lived in New York for part of a year, picking up with his old friends and adding new ones like reed player Ernie Caceres, whom he had heard on V-Disc overseas and been much impressed with. Returning to D.C., he led bands at the Charles Hotel, the Bayou, and the Mayfair, where as sit-ins or guest performers, Louis Armstrong, Wild Bill Davison, Dinah Washington, Hawkins, and many other jazz greats played with this widely respected musician. There were also some periods away from the area for Thomas, for example, playing trombone with clarinetist Tony Parenti in Florida and five years in Las Vegas with trumpeter Wingy Manone and several other bands.

“It isn’t like it was before,” says Thomas, comparing today’s [the 1980s] scene with that of the 1940s and 1950s. When he returned to the area in the early 1960s he found that the all-night jam sessions and the casual sitting-in were a part of history. In their place were “banjos everywhere, sawdust on the floor -- that was all the rage.” For a while “there wasn’t any demand for what we do.” But the jazz scene began to pick up in the mid-1970s and the idiom that Thomas has made his life -- hard-swinging 1940s jazz supplemented by slow-simmering ballads à la tenor saxophonist Ben Webster -- is much in demand in the 1980s. “I’ve been gigging around here with everybody since then,’ he says of the last decade[1970-80s].”

The presence of women instrumentalists in jazz at best making incremental progress — albeit almost totally so in combos and bands that they themselves are leaders of (and in which one finds many, and sometimes mostly, men) — it is clear that there should be no let-up in the effort to bring an end to this blatant form of discrimination in the jazz world. Women belong, and deserve to be, in the mainstream of the art form. That they are not is shameful. In fact, jazz is far behind not only American society but behind all other performing arts and all other musical genres in demolishing gender discrimination.

One of the most heartwarming expressions of concern about this salient issue was Nat Hentoff's Last Chorus column in the June 2001 JazzTimes. Titling his piece “Testosterone Is Not An Instrument,” Nat alluded to Lara Pellegrinelli's “scorching . . . indictment” of Wynton Marsalis’ Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra for excluding female instrumentalists from its ranks. Lara’s broadside originally appeared in the November 2000 Village Voice and reappeared in an updated version in the March 2001 JazzTimes. Titled, respectively, “Dig Boy Dig: Jazz at Lincoln Center Breaks New Ground, But Where Are the Women?” and “I Guess I Would Notice. But That Doesn’t Mean You Shouldn’t,” the VV article can be read online at villagevoice.com and the JT one at jazztimes.com. The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra remains all-male as of this essay's posting in March 2004.

Nat Hentoff quoted Billy Taylor as a strong supporter of women instrumentalists. “Time won't do it,” said Dr. Taylor. “There has to be an effort.” In a trenchant follow-up Letter to the Editor in the September 2001 JazzTimes, British jazz author Mike Hennessey commended Nat “for his condemnation of the pernicious and persistent discrimination to which female musicians have been subjected for decades.”

Nat also wrote, in the November 2003 issue of JazzTimes, a wonderful column on Diva. “If there were still big band cutting contests,” he said, “[Diva] would swing a lot of the remaining big bands out of the place.” (Nat’s columns can be found on line at jazztimes.com but the magazine's website does not run its Letters to the Editor column, so the published hard-copy issue itself will have to be sought for Mike's letter.)

Another splendid article is Monique Buzzarté, “View from New York: J@LC — Notice Something Missing?” on Newmusicbox.org. Buzzarté, a trombonist living in New York,specializes in new music. An author and educator as well as a performer, her advocacy efforts for women in music led to the integration of women into the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in 1997. Buzzarté’s article has some arresting links, e.g., “Orchestrating Impartiality: The Impact of 'Blind' Auditions on Female Musicians,” a study by Claudia Goldin and Cecilia Rouse published in the September 2000 issue of the American Economic Review, showed that the adoption of screened auditions in symphony orchestras resulted in an astonishing 50 percent greater rate of advancement for women from the preliminary to the semi- final audition rounds, and much greater likelihood that they would win in the final round.

Perhaps it's time to again mount the battlements. Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, which receives federal funding, still has no women in its ranks. (Anybody out there for a class action suit?) A wonderfully ironic commentary on all of this was provided by the recent occurrence of a "Jazz and Democracy Symposium" at the Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center, New York, on December 10, 2003. I haven't seen a transcript of the discussion so I don't know whether the absence of women in the LCJ Orchestra was cited as constituting a glaring contradiction of the symposium’s theme. One hopes that there was at least one gadfly in the audience who put the question to Wynton, “Where is the other fifty per cent of the populace in your ‘democratic’ orchestra?” (For some wonderful photographs of the event by Enid Farber, log onto www.jazzhouse.org and scroll down to Jazz Photos in the Gallery and then to “The Jazz & Democracy Symposium.”)

Two of my own books contain profiles dealing with this issue. In The Jazz Scene (Oxford University Press, 1991), Baltimore-based flutist Paula Hatcher discusses the status of women jazz instrumentalists as of 1990. In my Living the Jazz Life (Oxford University Press, 2000), Washington-area multi-reed and woodwind player Leigh Pilzer updates the scene a decade later. In the former book I “ghettoized” women in a dozen pages of the final, “Contemporary Scene,” chapter. Chided for so doing, I spread women throughout Living the Jazz Life. I take pride in the fact that, of the forty musicians profiled in the latter, eleven are women instrumentalists. My forthcoming (January 2005) Growing Up With Jazz (Oxford University Press) also contains profiles of some women instrumentalists from here and abroad.

Another issue that should be of concern to those who wish to see the elimination of gender discrimination in jazz is the ongoing, and flagrant, bias against women as critics of the music. Examine the mastheads of the leading U.S. jazz magazines and take note of the ratio of men to women writers and photographers. Down Beat has four women among the total of 58 contributors named, JazzTimes five of 61, Jazziz seven of 48.

Several years ago I was examining the list of those who voted that year in the annual Down Beat International Critics Poll and noted that only three women were among the 103 critics listed. This number of women has remained steady since then.

I might note that, about five years ago when I first counted the total critics involved in the Down Beat International Critics Poll, the number stood at 103. Last year's 113 indicates that, while the total has increased, those added have not changed the representation of women in the list. There were three in the 2003 list. I ask you, why did Down Beat not add ten women instead of swelling the male contingent?

The virtual absence of women among the critics for the Down Beat annual poll is a very serious, issue that should be addressed in an aggressive manner, not waiting for women to approach the magazine. I would conjecture that most women jazz writers would hesitate to do so, having already concluded that the Down Beat editorial staff and its contributing writers is pretty much a male preserve. Not a happy image in this day and time, eh?"